Zionism

Zionism is a multifaceted movement that encompasses a wide range of political ideologies and ideas, each of which has contributed in its own way to its development and significance within the Jewish collective consciousness.

Explore some of the most influential and well-known approaches that have shaped Zionist thought.

Zionist Approaches

Political Zionism: The Path to Jewish Sovereignty

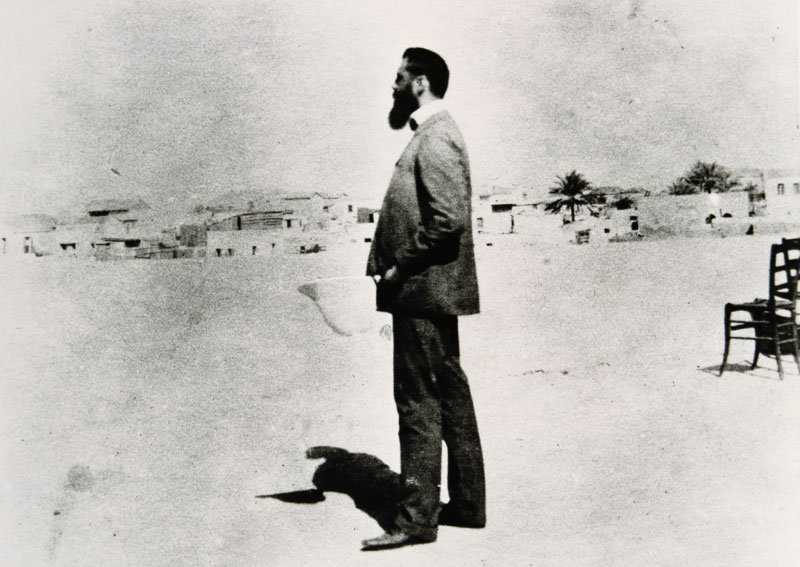

Political Zionism emerged in the late 19th century as a response to rising antisemitism and the widespread discrimination against Jews in Europe. This movement, shaped significantly by Theodor Herzl and supported by figures like Max Nordau, aimed to establish a Jewish homeland in the Land of Israel where Jews could live in safety and self-determination. It viewed Jews not only as a religious community but also as a people with a shared history, culture, and identity.

read more

The term “Zionism” was coined in 1890 by Nathan Birnbaum, a Jewish writer from Vienna. He later introduced the term “Political Zionism,” which referred to efforts focused on achieving a Jewish homeland through diplomatic negotiations and international support.

In his book Der Judenstaat (1896), Theodor Herzl argued that only a sovereign state could provide Jews with protection from persecution and offer a solution to antisemitism. While other locations for such a state were briefly considered, the Zionist movement ultimately remained committed to the Land of Israel—the historic homeland of the Jewish people.

Political Zionism was formally organized at the First Zionist Congress in 1897. This movement laid the groundwork for the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

Socialist Zionism: A Vision of Equality and Nation-Building

Socialist Zionism emerged in the early 20th century as a left-wing branch of the broader Zionist movement. It pursued the vision of establishing a Jewish homeland through the efforts of the Jewish working class, combining national aspirations with socialist ideals. This movement placed great emphasis on collective labor and social justice as the foundation for a new society in the Land of Israel.

read more

Inspired by thinkers such as Moses Hess, A.D. Gordon, Ber Borochov, and Nachman Syrkin, socialist Zionists believed that working the land was not only a means to physically rebuild the Jewish homeland but also a path to spiritual and social renewal for the Jewish people. Their focus was on creating a progressive society based on equality and cooperation.

A central element of socialist Zionism was the founding of kibbutzim—collective communities that combined communal living with shared labor and resources. These communities served as practical models of life based on socialist principles. Members of the kibbutzim—known as kibbutznikim—worked together, farmed the land, shared responsibilities, and built independent, self-sustaining communities. The kibbutzim attracted global attention and even drew non-Jewish volunteers who came to learn from and participate in these unique communities. Beyond their symbolic significance, the kibbutzim played a vital role in shaping Israel’s early economy, agriculture, and cultural identity.

Prominent figures in socialist Zionism included David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister; Golda Meir, the country’s fourth (and first female) prime minister; and Berl Katznelson, a key figure in shaping Israel’s early socialist identity. Socialist Zionist parties such as Mapai, which later evolved into the Israeli Labor Party (HaAvoda), dominated Israeli politics during the state’s first three decades.

Socialist Zionism viewed the creation of a Jewish homeland not only as protection from persecution and antisemitism, but also as an opportunity to build a society grounded in social justice, equality, and cooperation. While its influence was instrumental in shaping Israel’s early development, the movement also faced criticism—for economic inefficiency, ideological rigidity, and neglect of individual freedoms. Though its political dominance declined over the course of the 20th century, the ideas of socialist Zionism continue to resonate in Israel’s social fabric and cultural identity.

Revisionist Zionism: A Vision of Freedom and Strength

Revisionist Zionism emerged in the 1920s as a conservative current within the Zionist movement. Founded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the movement envisioned a Jewish homeland encompassing the entire historic Land of Israel—including territories east of the Jordan River (today’s Jordan) and the West Bank. Revisionist Zionism placed strong emphasis on military strength, national pride, and rapid Jewish immigration as essential means of securing sovereignty over the land.

read more

Jabotinsky called for a “revision” of the dominant Zionist policy at the time, which was primarily shaped by socialist Zionists. While those factions pursued negotiations and gradual settlement, Jabotinsky rejected such approaches. He believed that only determined and rapid settlement, supported by military strength, could enable the establishment of a sovereign Jewish state.

The revisionist approach also differed in its view of economy and society. Jabotinsky envisioned a nation based on individual liberty and a free-market system—contrasting sharply with the socialist ideals that defined the leading Zionist circles of his time. This made Revisionist Zionism the primary opposition within the broader movement.

Unlike the socialist Zionists, who sought cooperation with British authorities in Mandatory Palestine, Jabotinsky was deeply distrustful of the British. He was convinced that Jewish independence could only be achieved through self-determination—and, if necessary, through force.

After Jabotinsky’s death, his disciple Menachem Begin assumed leadership of the movement. He founded the Herut party, which later formed the basis of the right-wing Likud party. While Begin also supported territorial maximalism, he demonstrated political pragmatism—most notably in 1979, when he agreed to dismantle Israeli settlements in the Sinai Peninsula as part of the peace treaty with Egypt.

Revisionist Zionism left a lasting legacy, especially through the Likud party. Its focus was on upholding territorial claims and building strong defense capabilities, justified by the imperative of national security. These values continue to influence Israeli politics and identity to this day, attracting both support and criticism. Supporters see them as expressions of the right to self-determination and protection of the Jewish people, while critics associate them with rigid conflict positions and a reluctance to pursue territorial compromise. Despite these controversies, Revisionist Zionism remains a central part of Zionist history and development.

Religious Zionism: Faith, Nation, and Redemption

Religious Zionism views the founding of the State of Israel and Jewish sovereignty over the land as both a political achievement and a religious obligation, derived from the Torah and Jewish prophecies. It emerged in the late 19th century and was initially shaped by Rabbi Yitzchak Yaacov Reines, the founder of the Mizrachi movement. Later, the teachings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi in pre-state Israel, played a central role in further developing this current.

read more

A key point in the intra-Jewish debate was the question of whether human action could advance the process of redemption. While many Orthodox groups believed that the redemption of the Jewish people would only occur with the arrival of the Messiah, religious Zionists argued that settling and building the Land of Israel were active steps in that redemptive process.

Religious Zionism rests on three core principles: the Land of Israel, the People of Israel, and the Torah of Israel. The movement regards the return of the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland and the founding of the State of Israel as Atchalta De’Geulah—the “beginning of redemption.” While Rabbi Reines primarily viewed Zionism as a pragmatic response to antisemitism and the need to save Jewish lives, Rabbi Kook emphasized its spiritual and messianic dimension. He considered the Land of Israel inherently holy and believed that even secular pioneers were fulfilling a divine role in rebuilding the Jewish nation.

Over time, religious Zionism evolved. Following the Six-Day War in 1967, the movement took on a more nationalist orientation, emphasizing the religious and historical significance of territories such as Judea and Samaria (the West Bank).

Today, religious Zionism is a powerful force in Israeli society. It merges spiritual beliefs with political goals, continuing to shape Israel’s cultural and political landscape. Its adherents uphold a vision of a Jewish state grounded in religious values and committed to preserving the deep historical and spiritual connection between the Jewish people and the Land of Israel.

Cultural Zionism: Unity Through Language, Art, and Education

Cultural Zionism, founded by Asher Ginsberg, better known by his pen name Ahad Ha’am, was a current within the Zionist movement that focused on the renewal of Jewish culture, language, and spiritual identity.

read more

Ahad Ha’am famously declared that Zionism must aim to establish “a Jewish state and not merely a state of Jews.” He stressed that the state should be founded on a strong cultural and intellectual basis that would enrich the Jewish people spiritually, even before political independence was achieved.

A central component of cultural Zionism was the revival of the Hebrew language, a historically unique undertaking. For centuries, Hebrew had been used almost exclusively for religious texts and prayer. In everyday life, Jews spoke other languages depending on their region, such as Yiddish, Ladino, or the local language. This shift occurred after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, when the Jewish people were exiled and Hebrew lost its role as a spoken daily language.

The linguist Eliezer Ben-Yehuda led the movement to revive Hebrew in the 19th century. He believed that a shared language was essential for the unity and identity of the Jewish people. Together with his family, he created the first exclusively Hebrew-speaking household in nearly 2,000 years. Ben-Yehuda dedicated his life to modernizing the language. He compiled the first modern Hebrew dictionary, coined new words, and developed rules to adapt the ancient language to the needs of the modern world.

Thanks to his efforts, and with support from the broader Zionist movement, Hebrew became a living everyday language in the Land of Israel. It served as a unifying force among Jewish immigrants from many parts of the world and played a central role in the cultural revival and the creation of a cohesive national identity.

The legacy of cultural Zionism is still evident in Jewish culture today. In particular, the revival of Hebrew and the promotion of art, literature, and education have had a lasting impact on Jewish identity. Cultural Zionism remains an important part of the broader Zionist movement. It highlights the significance of a shared cultural foundation in uniting the Jewish people and strengthening their connection to the Land of Israel.

Diaspora Zionism: Support from Afar

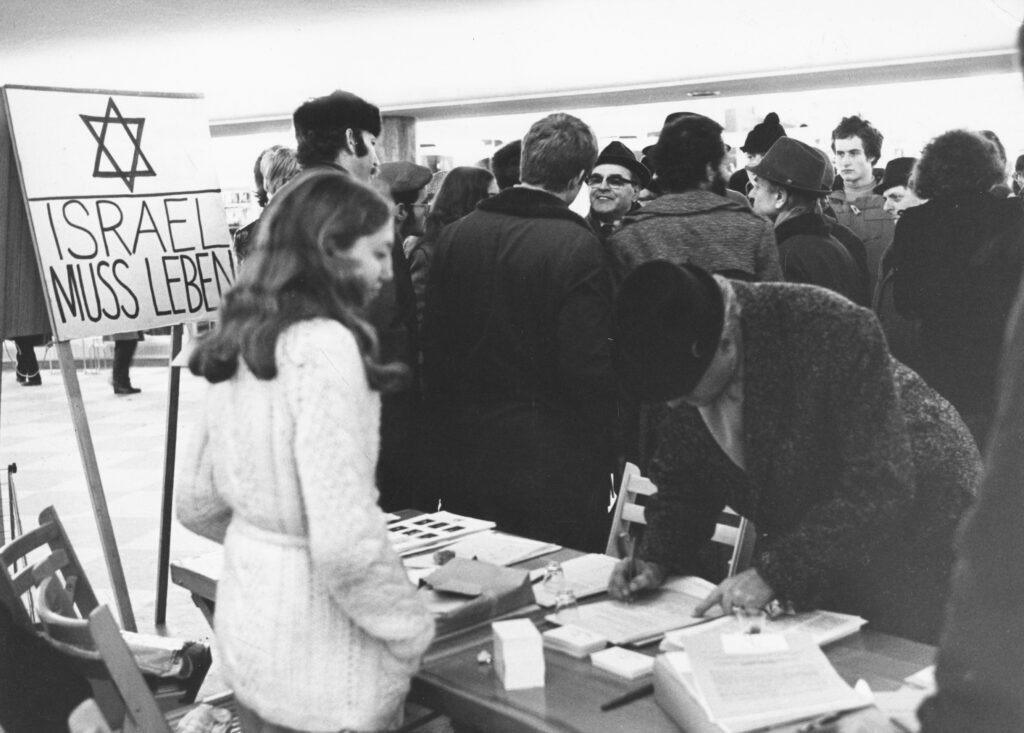

Diaspora Zionism focuses on fostering strong connections between Jews around the world and the Jewish homeland. Unlike other forms of Zionism that emphasize settling in the Land of Israel, Diaspora Zionism celebrates the ability of Jews living outside of Israel to support the Zionist cause while maintaining their national identity in their countries of residence. This stream emphasizes cultural exchange, mutual support, and a shared sense of identity among Jews globally.

read more

One of the most prominent figures of Diaspora Zionism was Louis Brandeis, a U.S. Supreme Court Justice and passionate Zionist leader. Brandeis argued that there was no contradiction between being a proud American and a committed Zionist. In fact, he believed that Zionism strengthened the sense of responsibility and citizenship among American Jews. “Let no American imagine that Zionism is inconsistent with patriotism,” he declared in 1915. He insisted that loyalty to one’s own country and support for the Jewish homeland could coexist. Brandeis compared the contributions of Jewish Americans to the Zionist cause with those of Irish Americans who supported Irish self-governance, and emphasized that supporting Zionism made one a better citizen and a better human being.

Henrietta Szold, another leading advocate of Diaspora Zionism, highlighted that a Jewish state would not only serve as a refuge for persecuted Jews, but would also benefit those living in more prosperous countries. She viewed the Jewish homeland as a source of spiritual nourishment—a center rooted in Jewish traditions and the ideals of universal peace.

Diaspora Zionists recognized that not all Jews would move to the Land of Israel, but they believed in the importance of building a homeland where all Jews could find safety, cultural renewal, and pride. Through financial support, cultural exchange, and political advocacy, they played a crucial role in advancing the Zionist movement.

To this day, Diaspora Zionism continues to connect Jewish communities around the world with Israel, fostering cultural and spiritual bonds and helping ensure that Jewish identity remains vibrant both in the homeland and throughout the Diaspora.

Definitionen

Geschichte

„Zionismus ist eine nationale Bewegung des jüdischen Volkes, die ihre Wurzeln im antiken Königreich Judäa und Israel hat. Seit der Zerstörung des Zweiten Tempels in Jerusalem und der anschließenden Diaspora lebte die Hoffnung auf eine Rückkehr nach „Zion“ das historische Zentrum jüdischen Lebens, in den jüdischen Gemeinden weiter. Historische Figuren, wie etwa Flavius Josephus dokumentierten das jüdische Leben in der Antike. Aus der Erkenntnis des Misserfolgs der Assimilation von Jüdinnen und Juden in den Ländern der Diaspora entstand die Erkenntnis der Notwendigkeit einer jüdischen Heimstätte. Durch Vordenker, wie Theodor Herzl entwickelte sich diese Erkenntnis und die Sehnsucht nach der Rückkehr in die Ursprungsheimat des jüdischen Volkes zur Entstehung des modernen Staates Israel im Jahr 1948.“

Religion

„Zionismus ist der Ausdruck einer tief verwurzelten religiösen Sehnsucht im Judentum nach dem heiligen Land Zion, das in der Torah 157 Mal erwähnt wird. Für gläubige Jüdinnen und Juden symbolisiert Zion nicht nur das geografische Jerusalem, sondern auch die spirituelle Verbindung zu G-tt, dem Schöpfer der Welt, wie sie im Tempel in Jerusalem zum Ausdruck kommt. Die Bedeutung dieses Ortes im jüdischen Glauben wird auch dadurch unterstrichen, dass jede Synagoge, überall auf der Welt nach Jerusalem ausgerichtet sein muss und sich jeder Betende nach Osten drehen muss. Im täglichen Hauptgebet werden außerdem die Worte „Zion“ und „Jerusalem“ jeweils fünf Mal erwähnt. Der religiöse Zionismus misst den in der Torah beschriebenen Orten im ehemaligen Königreich Judäa und Israel eine besondere Heiligkeit zu.“

Politik

„Zionismus ist eine politische Bewegung, die das Recht des jüdischen Volkes auf Selbstbestimmung und Souveränität in ihrer historischen Heimat, dem Land Israel, bekräftigt. Er betont das Recht auf Verteidigung und Selbstschutz angesichts des Antisemitismus und anderer Bedrohungen. Die Unabhängigkeitserklärung des Staates Israel ist eine Manifestation dieser politischen Bestrebung und ein Symbol für Demokratie, Emanzipation, Gleichberechtigung und Pluralismus, die im Zionismus als Grundwerte verankert sind.“

Identität

„Zionismus ist ein zentraler Bestandteil der jüdischen Identität, der die jüdische Widerständigkeit, das Selbstbewusstsein und die Stärke des jüdischen Volkes betont. Er ist eine Antwort auf Jahrhunderte der Verfolgung und symbolisiert das Nie Wieder-Versprechen, das viele Jüdinnen und Juden weltweit in ihrem Selbstverständnis tragen. Für die absolute Mehrheit der Jüdinnen und Juden weltweit ist der Zionismus eine wichtige Komponente ihrer kulturellen und nationalen, jüdischen Identität.“

Vielfalt

„Zionismus kann für Individuen unterschiedliche Bedeutungen und Ausprägungen haben, abhängig von ihrem Verhältnis zu Israel und ihrer jüdischen Identität. Für manche ist er der Ausdruck einer tiefen kulturellen und spirituellen Verbindung zu Israel, während er für andere eine politische oder soziale Verpflichtung darstellt. Im Kontext der Diaspora kann Zionismus auch den Wunsch ausdrücken, die kulturelle und nationale Identität des jüdischen Volkes in einer globalisierten Welt zu bewahren und zu stärken.“